*This text was written by a TecMundo columnist; finally learn more.

Throughout history, for countless centuries, the existence of planets beyond the boundaries of our Solar System (exoplanets) was mere speculation. This hypothesis became a reality a little over 30 years ago, starting in the 1990s, when science established its existence. Today, more than 5,000 exoplanets are known and catalogued, discovered by the effects they cause on the stars they orbit.

When we think of planets in general, our minds are filled with thoughts and images referring to gas giants or rocky bodies orbiting a parent star, such as those that exist in our own star system. In fact, there are hundreds of billions of stars in the Milky Way alone, some large and red, some small and white, each with its own history of formation and evolution. However, almost all of them have one thing in common: a planetary system.

Extensive detection of exoplanets (starting with the Kepler mission) has shown that it is not necessary to choose carefully by star type or some sort of special location to find objects like this. You’ll likely find a number of planets, not just one, in any star you look at. These and other results have led astronomers to estimate at least one planet on average for every star in existence.

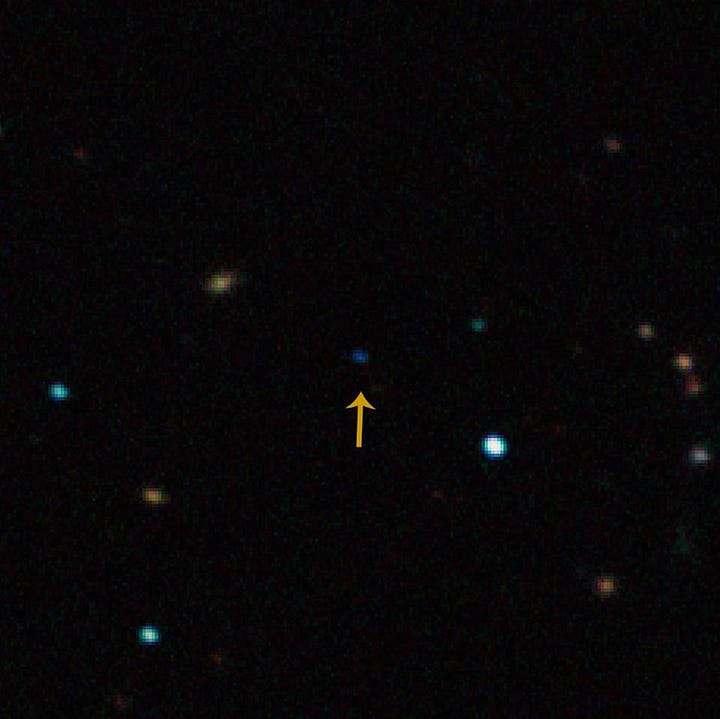

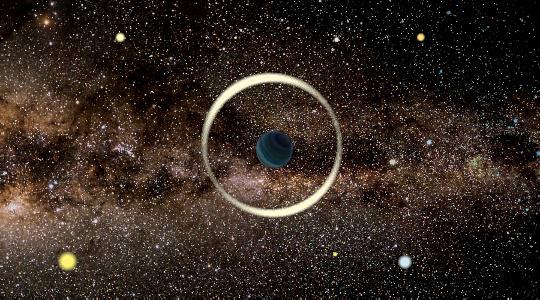

However, there is a class of planets that are little known but may be the most common type in the Universe: orphan planets or wandering planets. Curiously, these are planetary-mass interstellar objects that are not gravitationally bound to any stars or brown dwarfs and wander alone in space. But how is this possible?

During the process of forming a star system, the forming planets (and other objects such as moons and planetoids) gravitationally attract each other and tend to migrate over time to the most stable orbital configurations they can achieve. Typically this means that larger, larger worlds achieve their final position at the expense of other smaller, lighter worlds: in a battle for planetary supremacy, one of the most common consequences of forming planetary systems is the ejection of losers to Earth. space between stars.

In other words, orphan planets are thought to have formed mainly in early solar systems and were ejected due to intense gravitational interactions. Another way these planets form is in situ, namely through the gravitational collapse of matter in interstellar space itself, or as members of insufficiently large and failed solar systems.

Through computer simulations, astronomers estimate that for every Solar System like ours formed, there must be at least one gas giant planet and about 5 to 10 smaller rocky worlds that were launched into interstellar space where they would wander aimlessly and without home. galaxy.

This tells us, at the very least, that the number of starless planets is comparable to the number of planets orbiting stars today. However, these results are only for orphaned planets that were ejected from their main systems by the gravitational force of their siblings. Add in the planets that form in the interstellar medium itself, and the estimated number of rogue planets in our galaxy alone exceeds tens of trillions!

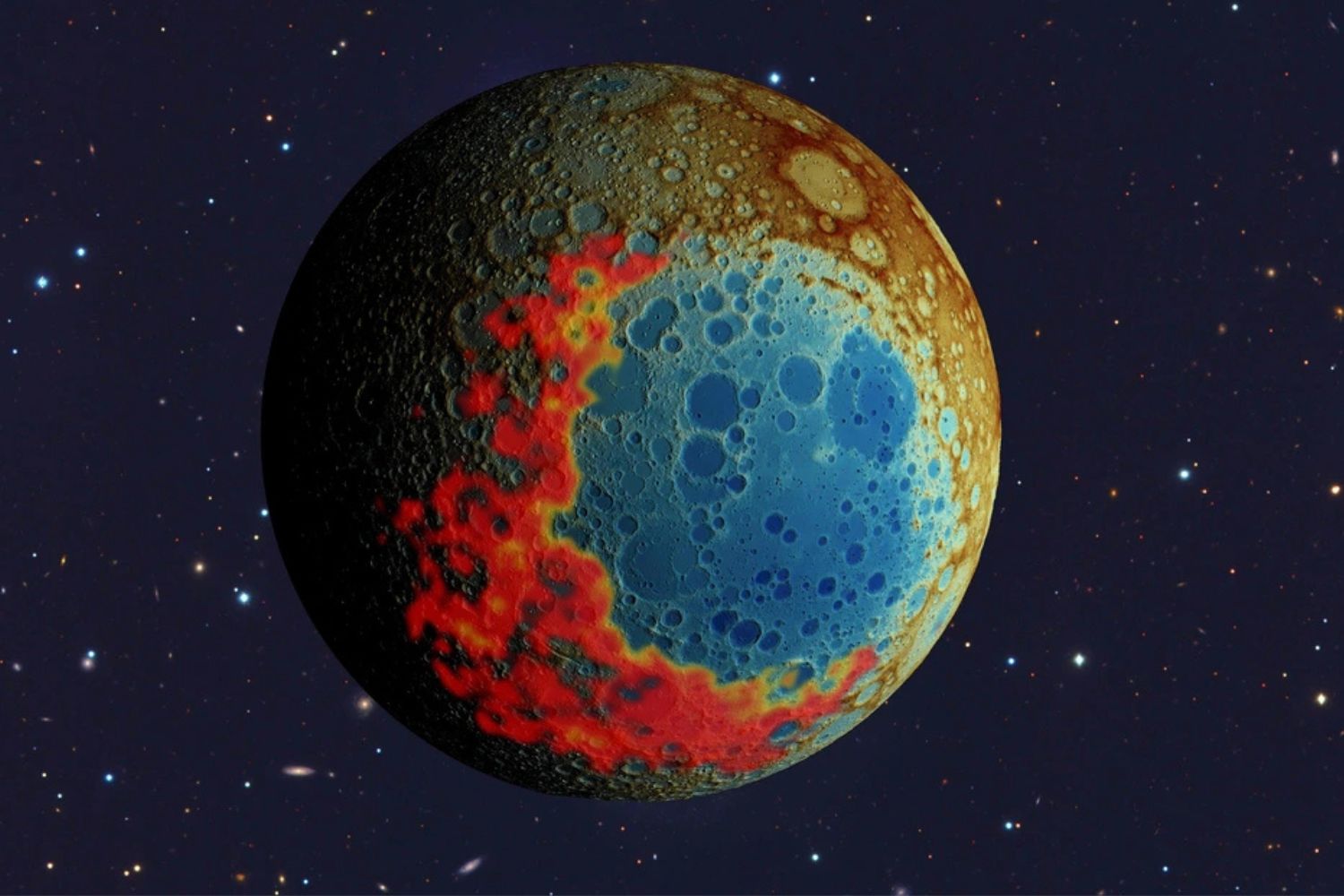

But if an orphan planet doesn’t revolve around any stars, how do we know they exist? In fact, it is nearly impossible to find lone planets in the visible light wavelength in the interstellar medium, as they do not emit their own light and do not reflect the light of any neighboring stars. For this, astronomers use infrared observations that capture the thermal radiation of these celestial bodies, or gravitational microlensing, which measures the distortion of light from distant stars as they pass by these planets.

If the statistical estimates are really close to reality, there is probably 100 to 100,000 planetary orbits for every star we can see. While a small percentage are ejected from their own star systems, the overwhelming majority have never known and will never know the temperature of the Sun. Some may arrive at a new system, possibly due to gravitational pulls. Who knows, some of them may even harbor life.

Whatever their fate, they will still continue to roam the galaxy for millions of years.

Nicolas Oliveiracolumnist for Technology WorldHe holds a degree in Physics and an MA in Astrophysics. He is a professor and currently doing his PhD working with galaxy clusters at the National Observatory. He has experience teaching Physics and Astronomy and researching Extragalactic Astrophysics and Cosmology. It acts as a popularizer and scientific communicator aimed at the dissemination and democratization of science. Nicolas is available on social networks such as: @nicooliveira_.

Source: Tec Mundo

I’m Blaine Morgan, an experienced journalist and writer with over 8 years of experience in the tech industry. My expertise lies in writing about technology news and trends, covering everything from cutting-edge gadgets to emerging software developments. I’ve written for several leading publications including Gadget Onus where I am an author.