A woman receives the brain of her unborn child. The result is a hybrid creature that sets out into the world to discover all it has to offer. Premise Poor creatures Yorgos Lanthimos is not easy, and the director does not make it easy to understand. What it does achieve is to turn this Victorian nightmare into a satire about the exploration of a very unusual desire. So much so that the majority his scenes fall somewhere between disgust, surprise and interest.

This isn’t the first time a director has achieved something like this. Their films have one thing in common: they are a mixture of dark humor and unpleasant stories. All told through complex scenarios that explore the gray and dark sides of human nature. He has already done this in Lobster, Most lovely and also, in Sacrifice of a sacred deer. Three arguments united by a pessimistic view of humanity. Each explores the great existentialist themes in their own way. Love, desire and death. But they never do it in a simple and accessible way.

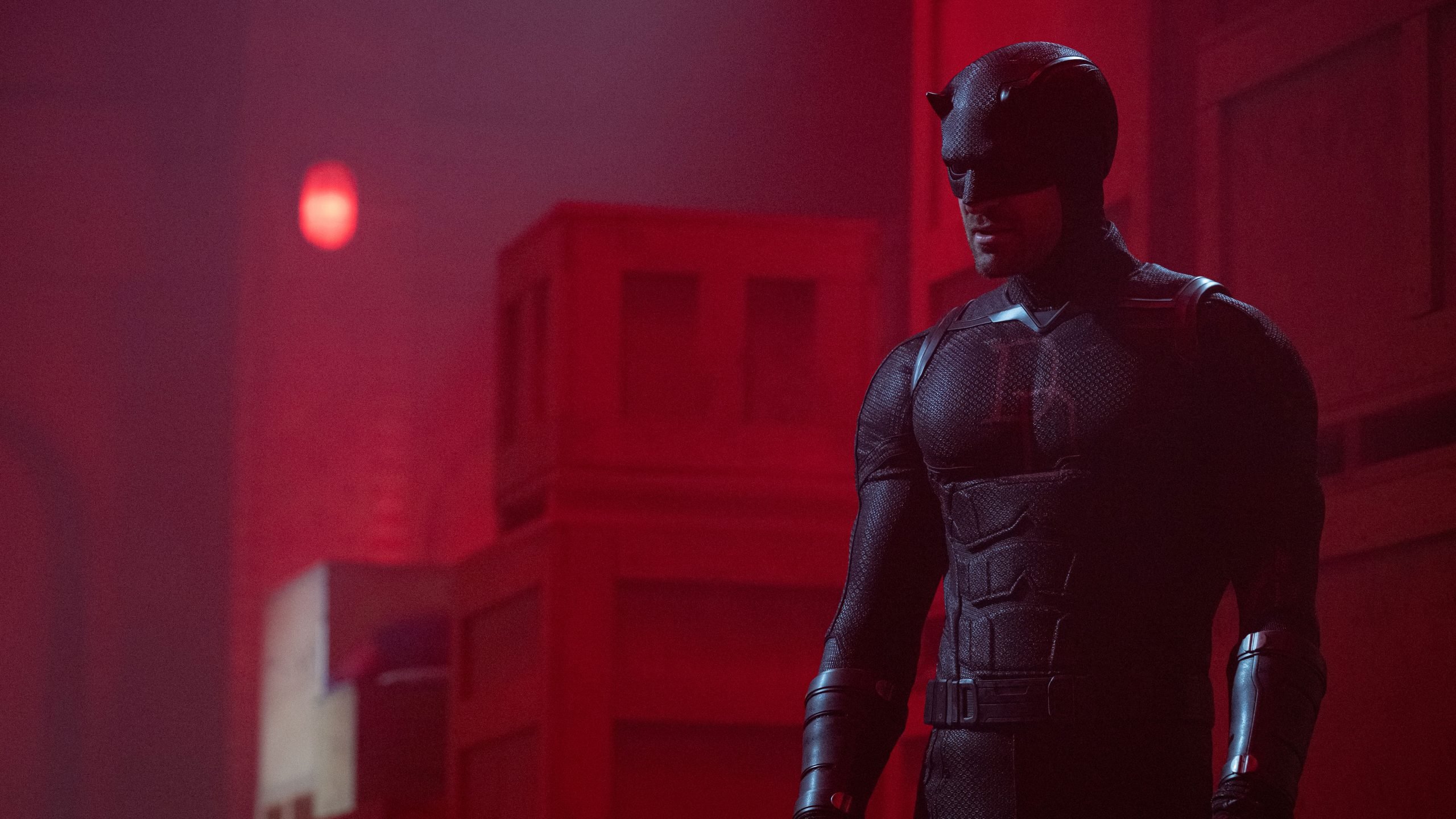

poor creatures

Mary Shelley’s twisted version of Frankenstein uses the novel’s central themes to explore a woman’s sexual and intellectual awakening. Additionally, examine the hypocritical and emasculating society of the 19th century as a symbol of modern culture. And all this in a carefully designed setting with a surreal atmosphere that surprises with its creative freedom and staging, full of dark details.

However, poor creatures, it’s far more than any other director’s obsession sublimated into good cinema. It is also a look at female power and the fear it breeds in a male culture. Even a study of maturity among an emasculating society. All this is combined in an argument so original that it is difficult to understand at once. One thing is clear: this version of Frankenstein is both grotesque and brilliant.

A repulsive and touching story

Combining the unpredictability of Tony McNamara’s script, based on the book by Alasdair Gray, published in 1992. The film is nothing like the usual women’s coming-of-age fables. At its core, the plot is a timeless chronicle of promiscuous sexual liberation, despite being set in the Victorian era. But this does not detract from the brilliance of its careful staging or its visuals, baroque and full of details reminiscent of steampunk. However, and unsurprisingly, the purpose of the film is to talk about the life Bella Baxter (Emma Stone, vying for her second Oscar). And that’s exactly what he stands for.

A life that, moreover, deserves to be told. Just as in the literary original, this young woman – an experiment and at the same time the result of an atrocity – is happy with the very fact of life. The cost doesn’t matter. But this appetite – to enjoy every minute of existence – is much more perverted than naive. Yorgos Lanthimos carefully avoids making his film a reminder of the goodness of the world in its primitive state or anything equally banal. Before that, Bella, she’s a force of nature. Clad in layers of fabric that suffocate her, this ferocious hybrid of monster and newborn creature seeks her target.

This is where the script connects to the story of Mary Shelley. Like Victor Frankenstein’s monster, Lanthimos’s monster asks questions about its purpose in the world. Is it just an experiment or a creature independent of its creator? To find out, you will have to leave him. Something that will force Dr. Godwin Baxter (an unrecognizable Willem Dafoe) to try to stop her. Then Bella will have to give up what she has known up to this point—and the man she recognizes as God—to examine her life.

There’s a messy, frantic joy to Emma Stone’s character. And this is without falling into sentimentality. What’s most striking about the film is its refusal to be pleasant or moving. Instead, this story of a creature born from the brain of a fetus and an adult woman forces the viewer to embrace discomfort. Some of his best scenes, involving sexual pirouettes and philosophical conversations about reality, are based on the grotesque. But gradually the director manages to combine the pieces of his personal adventure, turning it into a symbol of the pain and abuse to which the female sex is subjected.

Captivating visual finish

One of the most interesting aspects of the film is, of course, its visual part. Not just because of the meticulous detail of the historical recreation of a decadent and dusty London. And also because of the aesthetics surrounding its main character.

This embodiment of a pale Victorian woman with thick eyebrows and long black hair is also a ferocious creature of restless energy. What Robbie Ryan’s photographs reveal in a world created with your curiosity in mind. Glass jars containing stuffed animals rise in columns in a chaotic laboratory where a medical miracle takes place. A meter-high library with books in bright covers.

There is meticulous care in color palettes, fabrics and textures in both Bella, who moves through this dollhouse of gargantuan proportions, and her surroundings. An element that makes the film go a long way to determine what is important and what is not in this crowded environment. As Belle sheds layers of clothing, crinolines and lace—to free herself—the film also subverts the setting. Even the scarred face of his father/God becomes more beautiful and softer as his motives become clearer.

unforgettable film

Bella has a huge, thick scar that runs from the back of her head to her lower back. Finding out how this was caused will also be the thread that ties the entire plot together into a coherent story. At the final stage, when the character goes on an experimental journey in search of the meaning of life, the mystery is revealed. But beyond that, it comes dangerously close to a cruel joke. In the story, death and life are one and the same. And its main character is the golden mean between both things.

As the entire film is filled with music by Jerskin Fendricks, the film presents a bold interrogation of the fear of life and the origin of identity. But above all, it is a demonstration that his story – sometimes stunning, always very beautiful – is aimed at redemption. Not in the usual form of plots, which also tell stories about women seeking freedom. This time it’s a look at the desire to survive at any cost, avoid connections and find your place in the world. The greatest message of this rare work, which may be destined to become one of the best films of the year.

Source: Hiper Textual