*This text was written by a TecMundo columnist; finally learn more.

From time to time, fundamental aspects of nature need to be reaffirmed: the Earth is not a flat disk, but neither is it a sphere. More precisely, the geometric representation that best approximates the shape of our planet is a flattened spheroid, that is, a surface whose polar axis is smaller than the diameter of the equatorial circle. Replacing with offal: The Earth is “almost” a flattened sphere.

One of the first known records of determining the shape of the Earth through an empirical demonstration was made by the Greek sage Eratosthenes of Cyrene, who calculated the radius of the Earth in the 3rd century BC. Eratosthenes did this by means of simple geometric relations obtained by the shadows projected by the stakes in the two cities, Siena (present-day Aswan) and Alexandria, on the same day and time of the year. Since the distance between these two cities was known and the angles formed by the shadows could be determined, Eratosthenes was able to determine the size of the Earth.

Over time, not only the shape of our planet, but also the approximate shape of the other structures we enter (such as the Solar System and the Milky Way) have been improved and updated according to scientific and technological developments. However, among the many mysteries that have baffled astronomers and cosmologists for the past 100 years, there is one particularly deceptively simple yet functioning one at the height of our cosmic ignorance: What is the shape of the universe?

If we lived at any time before the 20th century, this question wouldn’t even make sense: It would probably never have occurred to us that the universe could have a shape, because we would have learned simple Euclidean geometry like everyone else. He imagined the school and the Cosmos as a simple expansion of three-dimensional space. Fortunately, humanity has come a long way in understanding the nature of physics and mathematics since then, and as we now know that space can be bent by the presence of matter and energy, this question is not only logical but of fundamental importance to modern cosmology. . .

The best answer to this today is: As far as we know, the Universe is flat in three dimensions. Our intuition, which tends to think of the cosmos as a superdimensional sphere, is in accord with the theoretical model favored by physicists and astronomers of the last century: The universe started from a point, expanded outward in all directions equivalently, and will expand. eventually reaches its maximum size.

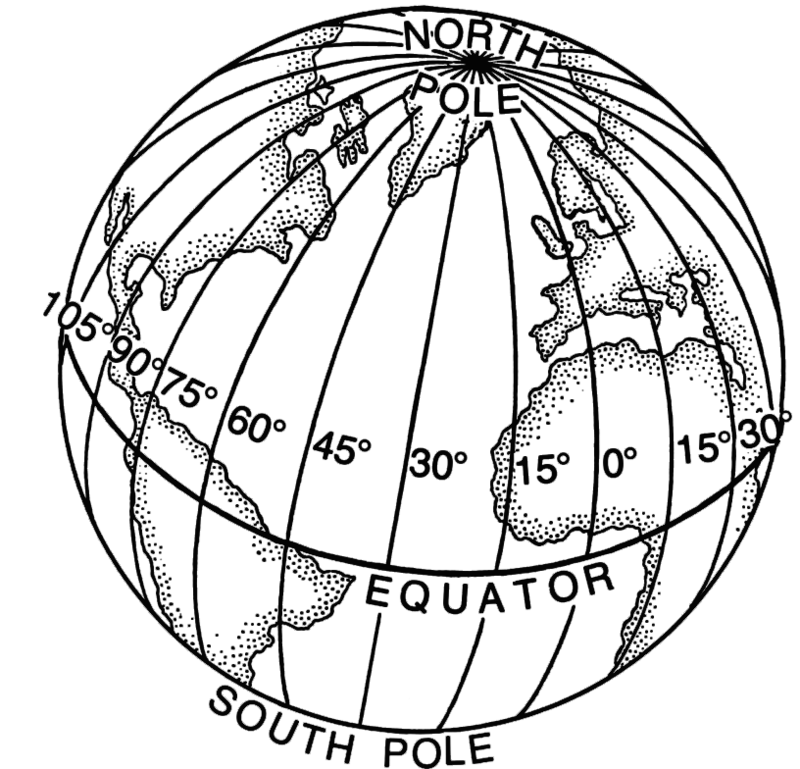

But since science is also made up of experiments and observations, a “flat” Universe is the answer we get. To understand this well, it is necessary to remember the simple concepts of Euclidean geometry that we learned in school mathematics lessons: two parallel lines never intersect, and the sum of the interior angles of a triangle is always 180 degrees. While everything we can draw on paper always follows these rules, these assumptions do not apply in every situation. For example, Earth’s lines of longitude are parallel at Equatorial height, but intersect at Earth’s North and South poles.

This is because there are actually three fundamentally different types of spatial surfaces: surfaces with positive curvature, such as a sphere; surfaces with negative curvature, such as a horse’s saddle; and surfaces with zero curvature, like a flat sheet of paper. So if we want to know what the curvature of the Universe is, all we have to do is “draw” a triangle on it and add the values of its three interior angles. If the result is 180 degrees, guess what?

In practice, cosmic geometry is predicted from the properties of the components that make up the Universe: electromagnetic radiation, ordinary (baryonic) matter, dark matter and dark energy. If the sum of all the densities of these components corresponds to a precise number called the critical density, the universe is flat. If this value is less than or greater than the critical density, the universe will have open or closed geometry, respectively.

In recent years and through different tests, observations of the components of the universe show that the universe is indeed very close to critical density, and therefore very likely to be flat. Because we don’t know exactly what dark matter and dark energy are, these measurements are constantly being recalculated, and our understanding of cosmic geometry is likely to change in the near future.

In any case, following our scientific progress, we will continue to seek more information about the Cosmos and the elemental aspects that make it unique.

Nicolas Oliveiracolumnist for Technology WorldHe holds a degree in Physics and an MA in Astrophysics. He is a professor and currently doing his PhD working with galaxy clusters at the National Observatory. He has experience teaching Physics and Astronomy and researching Extragalactic Astrophysics and Cosmology. It acts as a popularizer and scientific communicator aimed at the dissemination and democratization of science. Available on social networks like Nicolas @nicooliveira_🇧🇷

Source: Tec Mundo

I am Bret Jackson, a professional journalist and author for Gadget Onus, where I specialize in writing about the gaming industry. With over 6 years of experience in my field, I have built up an extensive portfolio that ranges from reviews to interviews with top figures within the industry. My work has been featured on various news sites, providing readers with insightful analysis regarding the current state of gaming culture.