After Wilhelm Röntgen discovered X-rays in 1895, the first radiotherapy sessions for cancer treatment began. The procedure involves beams of radiation directed precisely at the tumor to attack the DNA of cancer cells that are more sensitive to radiation and kill them.

But for a reason that has defied scientists’ understanding for decades, Radiation exposure kills the same tumor cells in different ways. This is important because some of these deaths go unnoticed by the immune system, while others trigger an immune response that kills any remaining cancer cells.

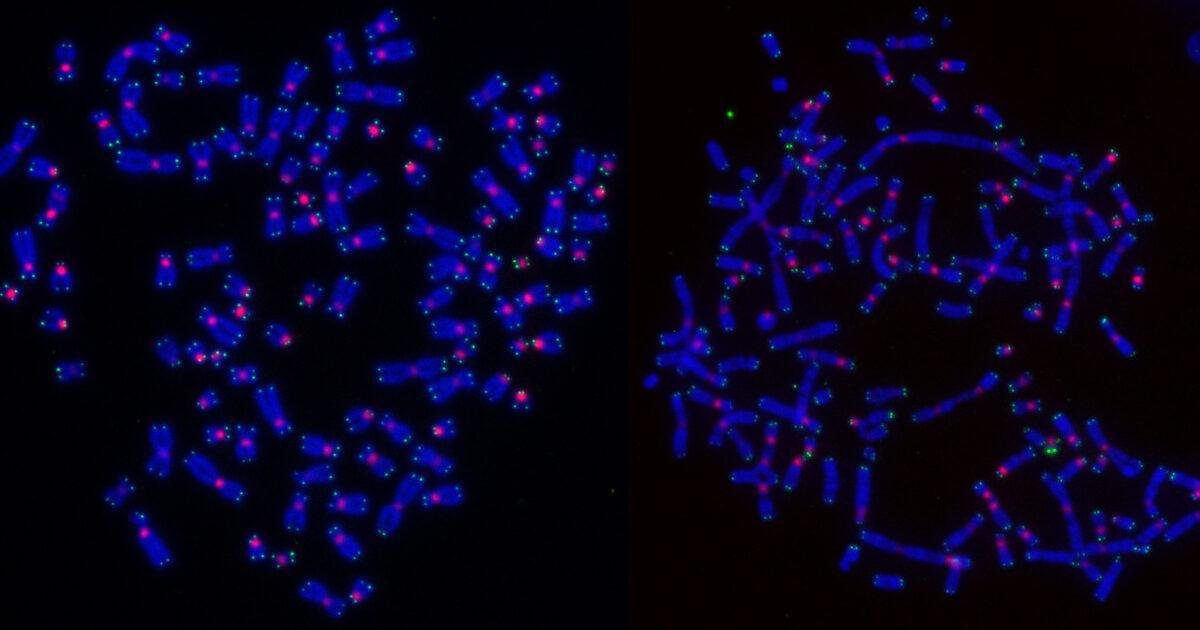

A study recently published in Nature Cell Biology claims to have solved this mystery. After researching this question for six years, lead author Radoslaw Szmyd, of the University of Sydney in Westmead, Australia, was able to solve the question after monitoring irradiated cells for a week using state-of-the-art microscopes.

How does radiotherapy work in practice?

In an ideal scenario, cancer treatment would free the patient’s immune system to kill cancer cells and clear tumors. To achieve this, radiotherapy, which kills some neoplastic cells, “reports” their presence to the immune system; This system directly kills radiation survivors.

However, this strategy fails, a literally lethal strategy for the survival of many patients. Why do some of these malignant cells die incorrectly?that is, it is not immunogenic. This means that some dies do only half the job and do not release signals that can activate the immune system.

“The surprising result of our research is that DNA repair, which normally protects healthy cells, determines how cancer cells die after radiotherapy,” says co-author Tony Cesare, professor at Sydney Children’s Medical Research Institute.

Why doesn’t DNA repair always recognize irradiated cells?

DNA, which forms the basis of the functioning of our cells, is constantly exposed to damage caused by natural metabolic processes, chemicals and radiotherapy. Although the genetic material corrects the damage, in the latter case the damage is so severe that the repair process itself recognizes the severity and gives “signals”. the cell begins to destroy itself (apoptosis)This makes DNA a tool in the fight against cancer.

If this repair could work to ensure that malignant cells do not die, radiotherapy would be harmless. However, in most cases the doses are calibrated to cause damage that the repair process cannot compensate for.

But Cesare says: “When DNA damaged by radiotherapy is repaired through a method called homologous recombination, cancer cells die during the process of cell division or reproduction, a mechanism called mitosis.” In these cases, death goes completely unnoticed by the immune system and does not stimulate an immune response.

How to activate the immune system in cases of death during mitosis?

The solution, the authors thought, was for the body to mount an immune response that could fight cancer more broadly. was to prevent homologous recombination (Repair mechanism that uses an intact copy of DNA as a template). Cells that have to repair themselves by other means are captured and killed by the immune system.

The hypothesis was tested in culture experiments and confirmed when the cells released interferons, proteins produced by immune system cells in response to viral infections and tumor cells. However, effectiveness still needs to be demonstrated in animal models and clinical trials.

Some drugs that inhibit homologous recombination, such as ATR enzyme inhibitors, may increase the effectiveness of radiotherapy, allowing doses to be reduced. A breast cancer-associated mutation in the BRCA2 gene also prevents homologous recombination and therefore death during mitosis. While another mutation accelerates repair, the authors are exploring new therapeutic strategies to improve treatments.

Did you like this discovery? Tell us on our social networks and take the opportunity to share the article with your friends and family. Until later!

Source: Tec Mundo

I’m Blaine Morgan, an experienced journalist and writer with over 8 years of experience in the tech industry. My expertise lies in writing about technology news and trends, covering everything from cutting-edge gadgets to emerging software developments. I’ve written for several leading publications including Gadget Onus where I am an author.